INTRODUCTION

EBITDA, which stands for Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization, is a powerful financial metric highlighting a company’s operational efficiency by stripping away the effects of financing, accounting, and tax decisions. It offers a transparent view of how well a business generates profit from its core activities. However, companies often turn to Adjusted EBITDA to get an even clearer picture. This refined metric goes beyond standard EBITDA by excluding irregular, non-recurring, or non-operational expenses such as restructuring costs, legal fees, or extraordinary losses. By focusing solely on the normalized earnings, Adjusted EBITDA provides investors and stakeholders with an undistorted insight into the company’s sustainable performance and long-term profitability potential. This nuanced approach allows for more accurate comparisons across businesses and industries, highlighting a company’s true operational strength and resilience. In this article, we will delve into what Adjusted EBITDA Margin is, how it is calculated using a real-life company example, the types of adjustments made, and the pros and cons of using Adjusted EBITDA.

WHAT IS ADJUSTED EBITDA AND ADJUSTED EBITDA MARGIN?

Adjusted EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization) modifies the standard EBITDA to account for unusual, non-recurring, or non-operational expenses and incomes. These adjustments can include restructuring costs, litigation expenses, or other significant one-time charges.

The formula for calculating Adjusted EBITDA is:

Adjusted EBITDA = Net Income + Interest + Taxes + Depreciation + Amortization + Adjustments for non-recurring items

Or,

Adjusted EBITDA = Reported EBITDA + Adjustments for non-recurring items

The Adjusted EBITDA Margin is then calculated by dividing Adjusted EBITDA by total revenue and expressing it as a percentage:

Adjusted EBITDA Margin= Adjusted EBITDA/Total Revenue ×100

KEY ADJUSTMENTS TO NORMALIZE YOUR EBITDA CALCULATION

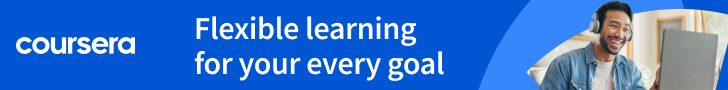

Normalizing adjustments to EBITDA involves adding or subtracting items to remove the effects of non-recurring, non-operational, or unusual events. These adjustments offer a more accurate view of a company’s operational effectiveness. Let us see the key adjustments made by Verizon Communications Inc. to its EBITDA to arrive at Adjusted EBITDA.

Source: Annual Report https://www.verizon.com/about/sites/default/files/2023-Annual-Report-on-Form-10k.pdf

The consolidated EBITDA of Verizon is $40,135 million in the fiscal year 2023. Below are some of the common normalizing adjustments made by Verizon to EBITDA to arrive at the Adjusted EBITDA:

1. Restructuring Costs: Restructuring costs are expenses incurred during significant changes in a company’s structure or operations, such as layoffs, plant closures, or reorganization. These costs are typically one-time and do not reflect the ongoing operational efficiency of the business. By adding back these expenses, EBITDA better represents the company’s normal operating performance. In the case of Verizon, the total restructuring cost includes – Business transformation costs of $176 million, Non-strategic business shutdown of $ 158 million, and Equity in (earnings) losses of unconsolidated businesses of $53 million added back to the EBITDA.

2. Severance charges: These are costs associated with employee layoffs or terminations, and are typically considered non-recurring expenses. When determining adjusted EBITDA, these expenses are added back to EBITDA to give a more accurate representation of the company’s core operational performance. Verizon adds back $533 million as severance charges.

3. Impairment Charges: Impairment charges, such as write-downs of goodwill or other intangible assets, are non-cash and non-recurring. These charges are added back to EBITDA to reflect the company’s ongoing cash-generating ability. Verizon adds back $5,841 as n Business Group goodwill impairment to the EBITDA.

4. Asset rationalization: Asset rationalization typically involves the sale, disposal, or write-down of non-core or underperforming assets. When calculating adjusted EBITDA, these activities are often considered non-recurring or one-time events. As such, adjustments are made to EBITDA to exclude the impact of asset rationalization, aiming to present a clearer picture of the company’s core operational performance. Verizon adds back $480 million to the EBITDA.

5. Legal and Settlement Costs: Legal fees and settlement costs that arise from one-time events, such as lawsuits or disputes, are not part of regular business operations. Including these costs in EBITDA offers a more accurate view of the company’s typical performance. Verizon adds back $100 million to the EBITDA.

6. Other non-recurring items: Some other non-recurring items of $313 million adjusted by Verizon include Pension and benefits re-measurement charges and Early debt redemption costs. Pension and benefits re-measurement charges are adjustments made to the value of a company’s pension and other post-employment benefit obligations, often due to changes in actuarial assumptions, discount rates, or investment performance. Early debt redemption costs are expenses incurred when a company repays its debt before the scheduled maturity date. These costs can include prepayment penalties, premiums, or the write-off of unamortized debt issuance costs. These charges can significantly impact a company’s financial statements but are generally considered non-recurring and non-operational.

Apart from the above adjustments some other common adjustments found in the calculation of Adjusted EBITDA are as follows:

7. Stock-Based Compensation: Stock-based compensation is a non-cash expense. However, the treatment of stock-based compensation is rather intricate, with numerous conflicting views. Since it is a non-cash expense, many companies calculate Adjusted EBITDA by adding it back to the reported EBITDA. However, as per the most prominent financial experts even though stock-based compensation doesn’t involve a cash outflow it shall be treated as a true operating expense and should NOT be added back to the reported EBITDA.

8. Extraordinary or Non-Recurring Items: These items include unusual events that are not expected to recur, such as natural disasters or one-time financial gains. Related expenses are added back, and gains are subtracted to normalize EBITDA. For example, in the case of COVID-19 extraordinary expenses incurred due to the pandemic, such as costs for safety measures or temporary shutdowns, are added back to normalize EBITDA.

9. Foreign Exchange Gains or Losses: Foreign exchange impacts are often non-operational. Subtracting gains and adding back losses help normalize EBITDA.

10. Non-Operating Income and Expenses: Non-operating items, such as interest income or expense, do not reflect core business activities. Non-operating income is deducted, and non-operating expenses are reinstated.

11. Personal Owner Expenses: Personal expenses incurred by the owner that are not related to business operations should be added back to normalize the earnings.

12. Below-Market or Above-Market Rent: If the rent is significantly below or above market rates, it should be adjusted to reflect market conditions.

13. Owner-Occupied Property Rent: If the owner occupies part of the business property for personal use, the personal portion of the rent expense should be added back.

14. Owners Salary and Benefits: If the owner’s salary and benefits are significantly higher than market rates or include one-time bonuses, the excessive or non-recurring portion can be added back to EBITDA to normalize earnings.

15. Understaffing: Understaffing refers to situations where a company does not have enough employees to operate at its full potential. This can lead to various operational issues, such as decreased productivity, increased overtime costs, and potential revenue loss. If the understaffing is temporary and non-recurring (e.g., due to unexpected events like a sudden pandemic wave or short-term labor strikes), the related costs and lost revenues can be considered abnormal and adjusted for in EBITDA.

IMPORTANCE OF ADJUSTED EBITDA FOR INVESTORS, COMPANIES, AND FINANCIAL ANALYSTS

For Investors

- Clearer View of Operational Performance: Focuses on core operations by excluding non-recurring and non-operational items.

- Comparability: Facilitates comparisons across different companies and industries, standardizing for variations in tax, interest, and depreciation.

- Valuation: Used in valuation metrics like EV/EBITDA, helping to assess the relative value of investment opportunities. This measure is especially valuable in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) for comparing the relative worth of different companies.

- Risk Assessment: Evaluates the company’s capacity to produce steady cash flow, which is essential for assessing risk and return.

- Identifying Trends: By tracking adjusted EBITDA over time, analysts can identify trends in a company’s operational performance. This helps in understanding whether the company is improving its efficiency and profitability or if there are underlying issues.

For Companies:

- Performance Measurement: Provides an internal measure of operational efficiency and profitability.

- Strategic Decision-Making: Informs management decisions on areas needing improvement or investment.

- Incentive Alignment: Basis for performance-based compensation, aligning management goals with shareholder interests.

- Communication with Stakeholders: Offers a transparent and standardized metric for reporting financial health to investors and creditors.

For Financial Analysts:

- Detailed Analysis: Helps in analyzing the true operational performance by excluding non-recurring items.

- Forecasting: Assists in creating more accurate financial models and forecasts by focusing on core business performance.

- Benchmarking: Provides a basis for comparing companies within the same sector or industry.

- Debt Servicing Capability: Evaluates the company’s ability to meet its debt obligations through operational cash flow analysis.

UNLOCKING TRUE VALUE: ADJUSTED EBITDA IN M&A VALUATION

When determining the value of a company for transactions like mergers, acquisitions, or raising capital, using Adjusted EBITDA provides a more accurate reflection of its core profitability. Suppose Company A has a reported EBITDA of $2 million but includes $300,000 in one-time restructuring costs and $200,000 in legal settlements. The Adjusted EBITDA would be $2.5 million. Using an industry average multiple of 6x for both EBITDA and Adjusted EBITDA, the valuation based on reported EBITDA would be $2 million x 6 = $12 million. In contrast, the valuation based on Adjusted EBITDA would be $2.5 million x 6 = $15 million. This higher valuation using Adjusted EBITDA acknowledges the company’s true operational performance by excluding non-recurring expenses, thus providing a more accurate and potentially higher valuation in transactions.

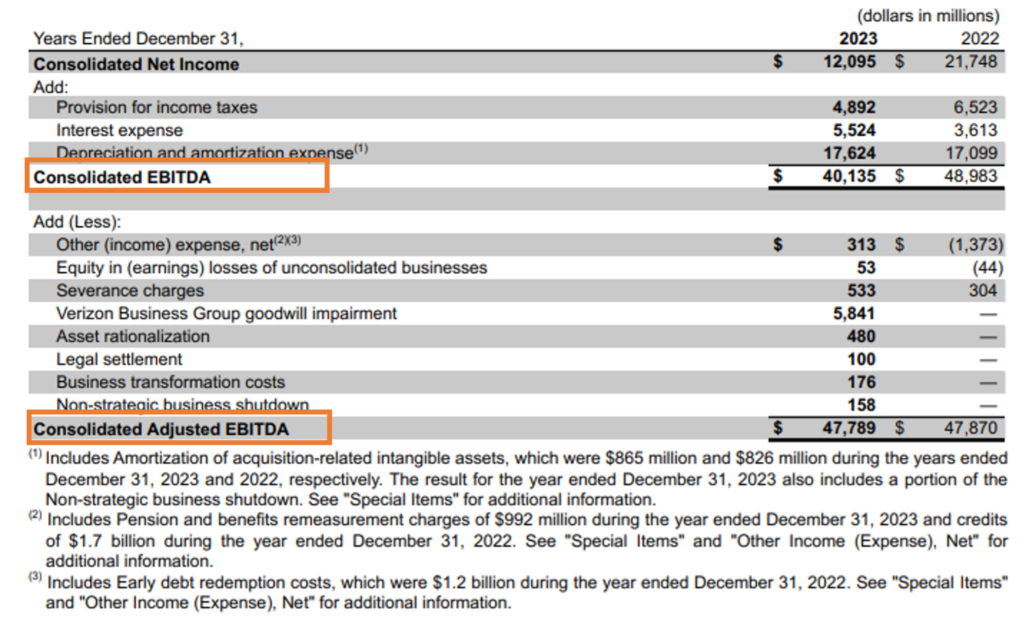

ADJUSTED EBITDA IS A NON-GAAP MEASURE

Adjusted EBITDA is a non-GAAP measure, meaning it is not defined or governed by Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). This flexibility allows companies to tailor the metric to better reflect their unique operational performance by excluding non-recurring, non-operational, and non-cash items. However, this lack of standardization can lead to inconsistencies and potential biases in how adjustments are made, making comparisons across companies more challenging. Despite these limitations, Adjusted EBITDA remains a valuable tool for assessing core profitability and performance, especially when used alongside other financial metrics.

Verizon discloses in its annual report that the Adjusted EBITDA is a non-GAAP measure as below.

Source: Annual Report https://www.verizon.com/about/sites/default/files/2023-Annual-Report-on-Form-10k.pdf

LIMITATIONS OF USING ADJUSTED EBITDA

Following are the limitations of using Adjusted EBITDA.

- Subjectivity in Adjustments: Adjusted EBITDA relies on management’s discretion to determine which items are considered non-recurring or non-operational. This can introduce bias and inconsistency.

- Exclusion of Important Costs: By excluding interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization, Adjusted EBITDA may overlook significant costs that impact a company’s long-term financial health and capital structure.

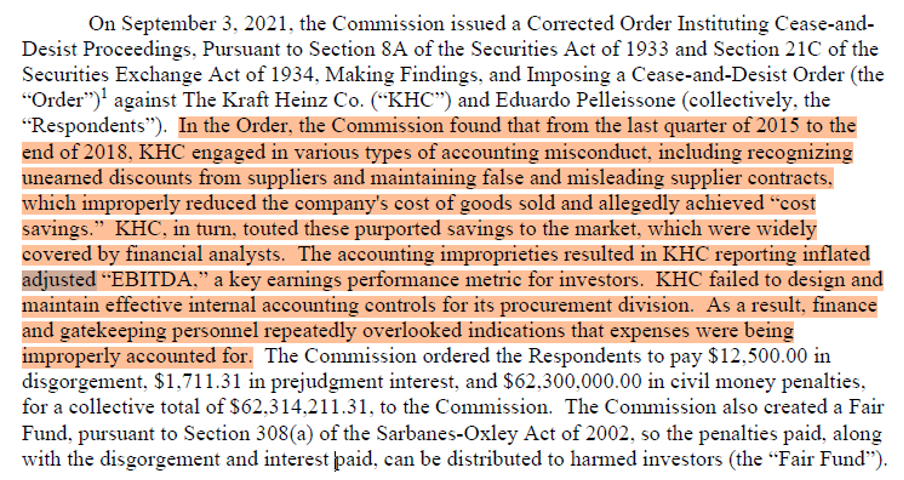

- Potential for Manipulation: Companies might over-adjust EBITDA to present a more favorable financial picture, leading to inflated valuations and misleading performance metrics.

Below is a case of inflated Adjusted EBITDA reported by Kraft Heinz Co. which led to payment of interest and penalties by the company.

Source: https://www.sec.gov/enforcement/information-for-harmed-investors/khc

- Lack of Standardization: There is no universal standard for what constitutes an adjustment, making comparisons across companies difficult and potentially misleading.

- Ignores Cash Flow: Adjusted EBITDA does not directly measure cash flow, which is crucial for assessing a company’s liquidity and ability to meet financial obligations.

- Doesn’t Address Working Capital: It overlooks changes in working capital, which can be a significant factor in a company’s operational efficiency and cash flow.

- Not a GAAP Metric: As a non-GAAP measure, Adjusted EBITDA is not subject to standardized accounting rules, reducing its comparability and reliability.

CONCLUSION

Adjusted EBITDA provides a clearer view of a company’s operational performance by excluding non-recurring, extraordinary, and non-operational items. Its advantages include improved comparability across companies and periods, better insight into core profitability, and aiding in investment decisions. However, disadvantages involve potential manipulation, lack of standardization, and sometimes obscuring actual financial health. Despite these drawbacks, adjusted EBITDA remains a crucial metric for assessing a company’s financial performance and making informed decisions. It offers a balanced approach to understanding true business operations, making it indispensable for analysts and investors alike.